At a recent conference presentation, I fielded the question:

“Isn’t UDL just differentiated instruction?”

I love this question. The strength of this question is that it provides an opportunity to help give shape to what UDL is and does so by relating UDL to a more familiar construct. It is, essentially, a compare/contrast question, a format that has been shown to be versatile and effective for higher order thinking (Silver, 2010).

This wasn’t the first time I had heard this question asked. In fact, I have heard at least three varieties of this question multiple times, whereby my colleague was interested in how UDL differed from accommodations models. Others have wondered if UDL could be accomplished in online environments by following WCAG 2.0 guidelines or other such accessibility-focused checklists. In this article, I want to explore how the constructs of UDL, Differentiated Instruction, Accommodations, Assistive Technology, and generalized Accessibility relate, overlap, and differ in signifiant ways.

Access… for whom? to what?

For me, the entire conversation revolves around the general concept of “accessibility.” It’s useful to consider that accessibility always has implied users and objects of accessibility; that is, when we speak of accessibility, we are discussing ensuring that certain individuals (users) have access to something (object of accessibility). The target user and object of accessibility call for removal of fundamentally different kinds of barriers.

For example, if the goal is to provide learners with physical access to a classroom, regardless of their mobility needs, then accessibility focuses on removing physical barriers such as narrow doorways and aisles, providing alternatives to stairways, etc. On the other hand, if the goal is to ensure that content is accessible for learners with varying sensory abilities, barriers may be in the form of static materials (such as print textbooks), with solutions ranging from the employment of assistive technology (such as reader pens) to proactive shifts toward use of digital material like e-textbooks that may be more accessible for diverse users.

And that’s usually where we stop.

These examples in the above paragraphs show the most common conception of accessibility. In this view, accessibility is “for” people with disabilities and provides access to learning environments and content/materials. One of the reasons we stop here is that this is the extent of legal mandate. ADA and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act, for example, are explicitly focused on individuals with disabilities and spell out anti-discriminatory regulations that in education contexts are mostly related to physical accessibility and content accessibility.

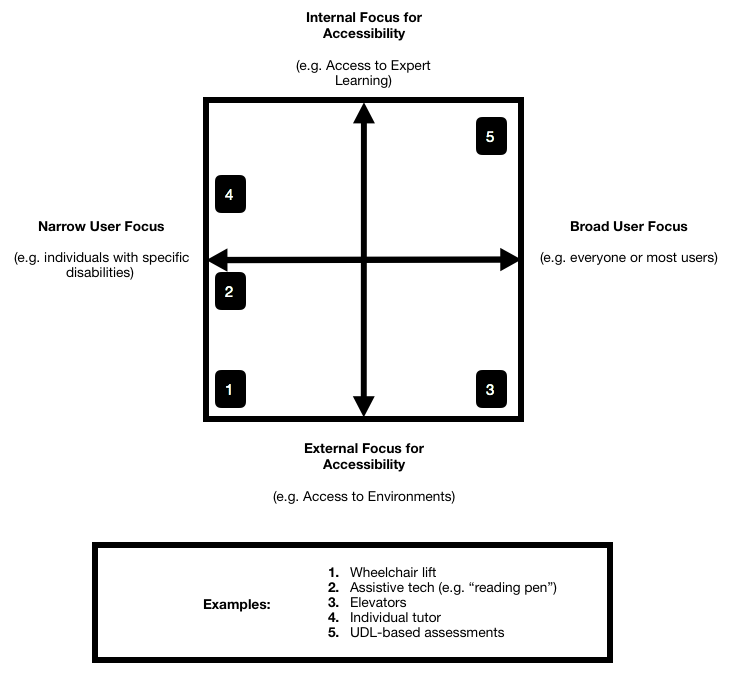

This narrow perspective on accessibility provides for predictably narrow beneficiaries, likewise. I don’t mean that these forms of accessibility aren’t important (they’re critical!) but that they are foundational for more universal accessibility (benefits for everyone, not just students with disabilities) and more internalized objects of accessibility (such as access to learning). Thus, in the graphic below, these points suggest that we have tended to focus on accessibility especially in the bottom left quadrant (narrow users, external focus), and almost exclusively in the bottom half (external focus). In our discussions of expanding accessibility, I mean expanding it both “upward” (more internal/cognitive objects of accessibility) and “rightward,” (more universal forms of accessibility).

To this point, I’ve tried to make two major points:

- Accessibility is a broad concept, far broader than we have traditionally recognized.

- Methods of providing accessibility can meaningfully be “plotted” based on the target user of the accessible service or design and the object of accessibility (that to which the user gains access)

Drawing Distinctions

These points lay the groundwork for differentiating among many approaches to accessibility. For example, in which quadrant(s) would you place assistive technology? Accommodations provided through student disability services? Where does the application of WCAG 2.0 guidelines for web design fall along the left-right continuum? Where would UDL be found? Try your hand with the concrete examples below.

[h5p id=”1″]

Analysis (Don’t look until you’re ready! Spoilers ahead!)

Note that “allow extra time on tests for a student with dyslexia” is a form of accommodation that enables one individual (narrow) student to demonstrate her knowledge (internal/cognitive) despite her need for additional time to read directions, etc.

Providing “preferential seating for students who need it” may be an accommodation for given students (for example, a student with a hearing impairment), but provides access to the learning content (external/environmenal) rather than to students’ own learning or expression.

“Sharing material on Canvas, not just in print copies” is not an accommodation because it doesn’t target any given student, it benefits all students (broad). This approach may provides students with access to the content in a flexible way that does not require holding onto a piece of paper and enables access nearly anywhere/anytime without having to have a physical copy on one’s person. In 21st century contexts (whereby students have their devices with them all the time), this is a best practice.

Finally, activating or supplying background knowledge in this case is applied to the whole class (broad), and enhances access to learning for the students, which places is firmly in the top-right. This is an example of one of the UDL checkpoints under the principle “provide multiple means of representation.”

We may draw a couple conclusions from what I am demonstrating in this exercise. Accommodations are always going to be on the left half of the graphic (they are always for individual/target students). Assistive technology is another form of accommodation, and likewise will almost always be on the left. On the other hand, UDL will always be on the right half (for all students) and is at its best on the top-right.

Note that context matters. If an instructor decides to provide a certain assistive technology device (e.g., iPads equipped with speech-to-text software) to all of her students, then the iPad ceases to be an assistive technology tool and becomes part of the classroom environment. If this is done to support variable learners in the class access the learning, then what was an assistive technology approach has become an application of UDL design. It isn’t the iPad itself that determines what kind of accessibility is provided, it is a matter of who has access and to/for what.

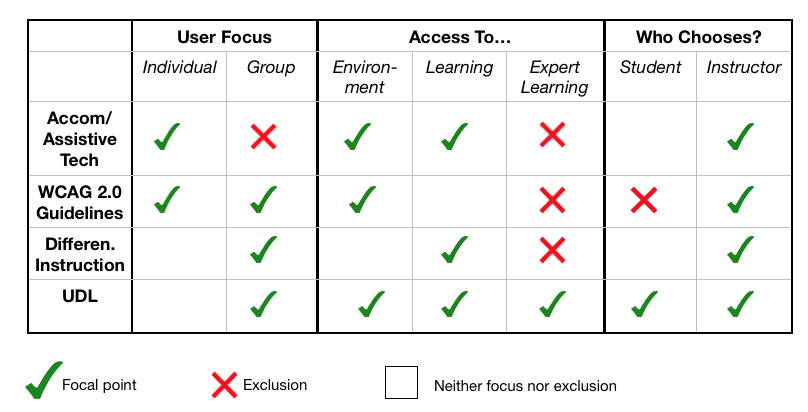

What about differentiated instruction? Differentiated instruction shares much in common with UDL. Unlike assistive technology and accommodations in our graphic, differentiated instruction would likely occupy the same space as UDL (the right half, mostly in the top right quadrant). We need a third aspect to parse UDL from differentiated instruction. That aspect is “choice.”

Who Decides?

A key factor discriminating UDL from Differentiated Instruction is the role of instructors and students in terms of decision-making. In a differentiated instruction environment, instructors think about an objective, then use data (usually casual observation or assessment data) to parse students into groups whereby they may be most successful. For example, an instructor may deliver a pre-test on the topic of atomic bonds and find that 3 students need remediation, four are ready for advanced study, and 12 who are “on target” for the lesson’s focus. She may then decide to divide the students accordingly during class, and have them complete different tasks based on where they are in relation to the topic.

Differentiated instruction has a long successful history in research and practice. It is worth noting who must do the decision making in this situation. In Differentiated Instruction…

[h5p id=”2″]When done well, these decisions can lead to significantly improved learning for students by providing appropriate challenge to everyone. But it does require a great deal of effort for instructors who are charged with all of that decision making. It also ignores student’s ability to make decisions (and doesn’t provide training to develop that ability).

UDL, on the other hand, is about putting choices in the hands of students as quickly and as much as reasonable, throughout the learning experience. For example, covering the same content of atomic bonds, the instructor in a UDL classroom may determine that she expects her students to have variable background knowledge. She may thus set a clear objective for the students to achieve that would prove rigorous even for the more advanced students. She may then provide a variety of instructional materials in stations around the classroom and online and use clear benchmarks for students to assess their progress toward the objective. She may provide a pre-test at each of the stations/in relation to each of the benchmarks to enable students to assess the degree to which they have mastered that point and decide how much time they need to spend on that particular station.

This example is just one way UDL may be applied and is contingent to the class, objective, and predicted student variability. The relevant point is to notice how the teacher’s choices were in all facilitative of student choices. Students in this situation made choices where the instructor did so alone in differentiated instruction.

Clearly, students will need some coaching with how to make these decisions at first, though the need for coaching will diminish as they become stronger in their self-awareness, goal-setting, resourcefulness, strategic ability, and motivation: all of which are involved in discussions of what is meant by “expert learning” in the context of UDL. Thus, in a UDL environment, expert learning is both a means and an end for instruction. Students will leave better equipped to self-advocate, self-teach, and self-motivate than in a learning experience driven by differentiated instruction, even if they learned the same content to the same degree.

Conclusions

Whew! In this post, we explored three ways to think about accessible design

- Who benefits (ranging from an individual to the whole class)

- To what do beneficiaries gain access (the environment, content, learning, or expert learning?)

- To what degree do students have choice in the accessible learning experience?

How we answer these questions helps us differentiate among different types of accessibility provisions. Assistive tech and accommodations focus on the individual to provide access to the environment and content, with instructors and others (e.g. student disability services) making most decisions. Differentiated instruction focuses on the group, an emphasizes access to learning (less: to content), but the instructor makes most of the decisions. UDL focuses on the group, with an eye to providing access to learning and expert learning by way of content, and involves a shared decision making experience between students and instructor.

These different approaches to accessibility have some overlap and some synergy. However, it’s important to see that they have different inputs (take different amounts of time from different people) and will lead to different outputs (student achievement in the subject and personally).

So, next time you hear “isn’t UDL just…”, I hope you’ll have some ideas for how to respond so as to give shape to the different models and can make choices as to which makes the most sense for a given situation, setting, and need!

Eric – fabulous post. Love the explanations and the interactive elements. Great touch to help emphasize the distinctions for the reader. It seems that you should also have a great “focal point” check for UDL within the “Environment” column. It may not be the “physical” aspects of the environment which represent barriers to learning, but there may be aspects of the environment for which the design needs to address and remove barriers to enhance the learning opportunities.

Thanks Steve! RE: Your comment regarding physical environments: I just set down to reading Liz Berquist’s new book (UDL: Moving from Exploration to Integration) and the first chapter drove this point home for me. A great point! I had always conceptualized those aspects of accessibility “pre-UDL,” but I definitely see now that UDL may be impossible or irrelevant if more basic aspects of accessibility aren’t addressed.

A very explicit approach to differentiate between the two Eric. I like the concept of using Quadrant . It helps planning your thoughts in the right place when choosing between the two.

Thanks

Harsharan Thethi